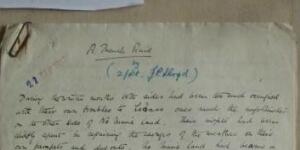

A Trench Raid - extract from the archive of MI 7b propaganda

Excerpt from A Trench Raid - article written for MI 7b(1) in September 1917, by Lt J P Lloyd of the Welch Regiment with a brief review.

The following extract is taken from MI 7b, the discovery of a lost propaganda archive from the Great War.

A Trench Raid

At last, after what seemed years of waiting, the long-expected signal came, and we filed into the sap, and then crawled cautiously across No Man’s Land to the shelter of some friendly shell-craters about forty yards from the Boche wire. The signal for the final rush was to be an intensive bombardment on the flanks of the position we were to attack.

We did not have to wait long. Punctual to the second, the artillery strafe commenced and simultaneously a blinding sheet of flame and an earth-shaking roar told us that H.E. had completed the work of our wire cutters in blasting a gap in the entanglements. The next few minutes were crowded in the extreme. The whole party made a dash for the opening in the wire, scrambled over the parapet, and, as had been arranged, divided their forces, and bombed their way, right and left, down the trench. A sentry, who had been posted quite close to the point of entry, had been blown backwards off his perch by the force of the explosion, and was no longer in a condition to dispute our passage. The only real resistance we encountered was on the right where a machine gun team hurriedly dismounted their gun from its emplacement, and directed a stream of bullets down the trench in the hope of catching the attackers unawares when the rounded the traverse. But the Bombing Sergeant, crawling along the parapet, dropped a couple of Mill's Bombs in the middle of the party, and then jumped down afterwards lest there should be any mistake. So it was that a battered machine-gun, plus a pair of stout Bavarians, very much the worse for wear, were shortly being passed to the rear.

Naturally the time is limited on a raid, and it is prudent to get back to the shelter of your own trenches before the enemy has time to recover from his surprise, and starts to retaliate. But before we turned back we lighted the fuse of an infernal machine which had been part of the R.E.'s contribution to the night's entertainment, and placed it in an unobtrusive position at the foot of the traverse, with the object of discouraging any Huns from annoying us in our retirement. We returned to the original starting point to find the moppers-up had lured several unwilling captives from their under-ground funk-holes, and had already started to shepherd them across No Man's Land on the first stage of their journey to England. As we picked our way through the shell-holes on our way home, our machine-guns were sweeping the Boche parapet on our right and left to restrain any vulgar curiosity on their part as to the fate of their brethren. The last of the excursionists dropped over our friendly parapet just as two infernal machines, in quick succession, rent the night with the roar of their explosion, and a salvo of woolly bears, the first fruits of retaliation, burst high up in the air over the ground we had just vacated.

The article, “A Trench Raid” was written by Lt J.P. Lloyd of the Welch Regiment in September 1917, and is one of 150 or so articles and stories he wrote. His work is the sole surviving archive of military propaganda from a secret outfit designated MI 7b. All the official documents of MI 7b were thought to have been destroyed at the war’s end.

Lt James Price Lloyd was my paternal great uncle and as a Second-lieutenant, he had been shot and wounded in the first Battle of the Somme in the fighting at Mametz on Friday, the 7th July 1916. Whilst recuperating, he responded to a War Office trawl for officers to write articles about the war. His work was accepted and on 7th July 1917, a year to the day since he had been wounded, he reported for duty with MI 7b.

He thought he was joining a unit set up to counter Hun propaganda, but that was just a cover story. Although he didn’t know it at the time, he was joining a strategic propaganda offensive aimed directly at the Home Front, and the home fronts of the Empire, her dominions and colonies. Allied nations too were targeted, as were neutral nations who needed to be swayed towards our cause.

MI 7b (1) had been set up in response to the perceived threat that support for the war was waning, that revolution was in the air, that there was discontent in the factories, and saboteurs active amongst us! In the autumn of 1916, through to the dread dark days of early 1917, disaster loomed. The nation, traumatised by the horrendous losses on the Somme front, faced insurrection in Ireland, revolution abroad, and was in danger of losing the battle at sea. The fear of losing the war and the prospect of famine brought home the reality of a modern, total war. To have any hope of preparing the nation not only to accept the huge losses that the strategy of attrition would inevitably demand, but also to sustain their faith that the cause was just and noble, and the sacrifice necessary, there had to be a counter-balance to the Roll of Honour.

The authorities recognised that they had to seize the agenda, set the tone, improve and sustain morale. To that end, the War Office trawled for officers with some time on their hands to write about the war, especially the human interest side. Capt Alan Dawson fielded their submissions and set up what became MI 7b (1).

It attracted some of the finest literary talent of the day, many of whom were serving in the Army and had connections to the popular newspapers and magazines of the time. Similarly illustrators and artists were recruited and so it was that MI 7b (1) was able to produce high-grade propaganda material in both graphic and text media from the outset. Given its connections and the newspapers’ insatiable appetite for war news, MI 7b (1) became a major source of news that was then reported by the press all over the English speaking world.

From August 1917, Lt James Lloyd wrote first-hand accounts of battles and daily life in the trenches, and Captain Bruce Bairnsfather provided cartoons and illustrations that gave the imagination a visual hook. It is clear that their work was integrated as a result of a clearly developed editorial strategy. Bairnsfather’s cartoon character “Old Bill” and his “Fragments from France” were a national sensation – Old Bill became the archetypal “Old Contemptible” and a much loved figure world wide. Lloyd’s retrospectives on fighting in France, along with Bairnsfather’s illustrations, allowed those on the world’s home fronts to identify with the men at war, and get that much closer to what they thought the war may be really like.

Lloyd had much to learn about writing propaganda as many of his drafts were too close to reality to have been passed fit for publication. Some of the most poignant and moving accounts he wrote, never made it beyond the manuscript. These “rejected” articles contain much that would otherwise remain hidden. In my view, these articles are that much more interesting and shed a truer and brighter light on events that went unreported.

As the propaganda agenda moved on, Lloyd was tasked with producing “Tales of the VC”, and so that his reports on the fighting in France weren’t stale, he was sent back to the Western Front to observe first hand. It is clear that Lloyd wasn’t the only MI 7b officer to undertake such travels, as A A Milne, too, undertook secret work in France at some time during 1918. Officers from MI 7b travelled the Western Front extensively witnessing, as opposed to taking a further active part in, the battles and major campaigns of the war from early 1917 onwards. Those accounts were their main source of war news reporting and were then distributed for publication around the globe. There are examples of newspapers carrying 2 or 3 articles sourced from MI 7b on a single page.

With War Office support, what had started out as a “one man and his dog” operation in early 1916, became a highly successful broadcast medium with global reach within 18 months or so, producing an estimate of 7,500 articles for syndication world wide. Had the “Green Book” – the secret valedictory house journal of MI 7b (1) - not been discovered by chance, those writing for MI 7b (1) would have remained incognito, and its secret work only imagined, as so little of its official archive is known to exist. A A Milne is now the best known member of MI 7b, and the current media interest in his role risks eclipsing the wider story. Milne was not the only surprise to be found on the inside cover of the Green Book, posted elsewhere on this forum. The list of members and their literary achievements is truly astonishing.

The 150 remaining articles in the archive are of a high literary standard and the articles and stories each stand on their own merit. They would be interesting enough on their own, but in the context of their being examples of a secret campaign, they are an invaluable source. Written by someone who had served and been wounded in the front line trenches, Lloyd’s stories provide a fascinating glimpse into the realities of the fighting, and of life in France. His published work for MI 7b (1) is extensive, and I am very grateful to everyone who has helped me find examples. However, not everything was published, and the unpublished drafts provide tantalising glimpses into the realities as perceived at the time and written in the lingua franca of that era with its richness of slang, its wry observations on the detail of daily trench life.

It is also fascinating to view the propaganda production process in action; from idea to pencil draft, to manuscript and green-ink correction and censorship, to the typing pool and beyond to the higher echelons of the War Office food chain where it may be “Passed for publication.” Then, the article is there on the page of a Tasmanian journal, sitting alongside other articles from MI 7b. Each of the articles are under the name of the serving officer who wrote them giving no indication that they are the principal parts of a highly secret and sophisticated propaganda offensive.

If the newspaper articles indicate the scale and reach of the operation, the discovery of the Green Book indicates the calibre of its operatives and like the Rosetta stone, unlocks some of the mystery.

Why were so many talented and intelligent men willing to write propaganda in support for a war that each of them knew would result in further widespread slaughter? I believe that that they knew it to be their duty. They were recruited ostensibly to take part in a counter-propaganda offensive, and although that may have been plausible for a while, it is clear from what is written in the Green Book, that by the war’s end, some of these were men who felt that their integrity had been compromised.

If all their work was meant for publication, what was the secret? The real secret of MI 7b (1) was that the Crown and Parliament had a very great need for it, far greater than history may yet have acknowledged.

Why was it disbanded so quickly? The rapid disbandment of MI 7b did not affect its role and function, for that carried on. I think that Lords Northcliffe and Beaverbrook recognised that MI 7b (1) was a first class news agency with global reach, in effect, the information superhighway of its day. They took control of its infrastructure to further their newspaper interests, and MI 7b’s role and function morphed via the Ministry of Information through to the BBC.

From Adelphi House to Bush House!

With its records destroyed, and all its members bound by the Official Secrets Act, the story of MI 7b (1) might have remained an interesting, but obscure, footnote in history. With any luck, this discovery may yet inform our thinking about the First World War, and play a significant role in our understanding of the true nature of the conflict and the context in which it was reported.

CONTRIBUTOR

Jeremy Arter

DATE

1917-09

LANGUAGE

eng

ITEMS

1

INSTITUTION

Europeana 1914-1918

PROGRESS

METADATA

Discover Similar Stories

MI 7b (1) Original manuscript from September 1917

1 Item

An original manuscript from a large archive of documents that are thought to be the sole remaining official documents from MI 7b. Discovered by chance, the archive was written by my great-uncle, who kept his original work at home. At the end of the war, all the official documents of MI 7b were destroyed by official order, but these documents survived.

Trench art from a German shell casing

1 Item

Attached to this story is a gold matchbox holder from the Battle of the Somme. The name A. Lynch can be seen on the front of the case along with a floral design which extends to the spine and the back of the casing. On the back of the holder a carving of Somme 1916-1917 can be seen surrounded by the floral design. || This story is about an anonymous soldier who used to work for my grandfather Anthony Lynch before he went to fight in the great war. The unknown soldier used to be an estate agent from Verschorles, Ireland before the war. During the war he fought in the Battle of the Somme. During the Battle of the Somme he handmade a matchbox holder out of an old German shell in the trenches. He personally created the design of the matchbox holder and carved my grandfather's first initial and surname onto the front of the case. When he returned home from the war he gave the gift to my grandfather's farm hand who delivered it to the family home in Clonyn Castle, Co. Kildare, Ireland. This matchbox holder was then given to Anthony's daughter Angela who then passed it on to her son. Unfortunately, the name and details of the soldier has been lost through the years.

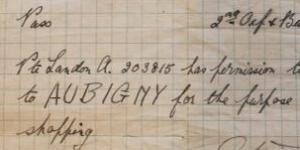

The Trench Chapel

6 Items

Photograph of post office and chapel built by Alfred Landon in the trenches Pass to collect food rations Details of military service with the Oxford & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry Cologne razor and cover || Alfred Landon was my father; he was one of five brothers who served in the war, 4 in the army and 1 in the navy, all of whom survived. By profession, Alfred was a baker and confectioner and in 1915 he enlisted in the Oxford and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry. He was gassed once, suffered trench foot at least twice and fought in several battles of Ypres. He said everyone got religious in the trenches and a trench chapel, St Peter's Chapel, was built at his instigation, also a trench post office. I'm not sure where they were. He got to Koln and brought back a cut-throat razor, his only souvenir from the war. He died in 1981. || || A pass issued to Alfred Landon to allow him to go the a nearby town for rations; paper, hand-written in ink with regimental stamp. || A pass issued to my father Alfred Landon || Pte Landon A. 203815 || Aubigny || Official document || || A photograph of St Peter's chapel in the trenches || Religion in the trenches || This photograph shows St Peter's chapel which was built into the side of a trench at the instigation of my father Alfred Landon; it is hard to see but there was also a post office and the notice board for services is just visible. The date at which is was built and the exact location are unknown. || Photograph || || Souvenir of Cologne || A cut-throat razor, case inscribed 'Souvenir of Koln' with a picture of the cathedral towers engraved on it; obtained by my father Alfred Landon during the war and his only souvenir. || Front