George Fredrick Harvey's war in the shiny seventh

Like many men who lived through the First World War, Granddad didn’t talk much about it, and I was too young to have developed my later interest in military history, so didn’t cross-examine him. So reconstructing his army career is a mixture of the odd anecdote I remember him telling me, and some background research. Granddad enlisted into the 7th City of London Regiment. He always referred to this regiment by its nickname, the ‘Shiny Seventh’. It seems odd that he joined a London regiment; at the time he was living in Ipswich. However, the 2/7th London Regiment were stationed in Ipswich from 19 June 1915 to 13 July 1916 , so he may just have decided to join the nearest regiment. However, his regimental number (7244) falls within the pattern of four-figure numbers used in the 1st Battalion – all the 2nd Battalion men I have traced had 6-figure number. He married my Grandma Ethel in Ipswich on 13 March 1915, so must have been newly-married when he joined up

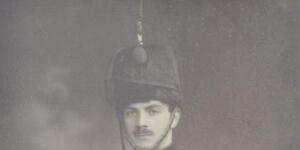

There is a photograph of him which almost certainly was taken as soon as he was issued his uniform: it looks bran-new. Mum said that when she was little he used to kid her that it was taken when he was in camp – there is a tent in the background, but it is obviously a painted backdrop of the kind commonly used by studio photographers.

I think I remember Granddad saying that he entered France through Le Havre. He said he liked the French people he met, but didn’t like the Belgians at all, for some reason. Having worked as an ‘oil carman’ (i.e. delivering paraffin on a horse-drawn cart), he was assigned to the regimental transport section at some time, although one of his anecdotes suggests he spent time in the trenches. He told me that one day an aeroplane flew over their trench, and he took a pot-shot at it with his rifle. The sergeant told him off and said it was ‘one of ours’ – while they were arguing the plane returned, and the black crosses on the wings were clearly visible! Although service in the transport section was a little safer than with the front-line companies, it could still be hazardous. When he was part of a convoy one night driving horse-drawn wagons, taking supplies close to the front-line, and well within German artillery range, they came to a cross-roads. The Germans were slowly and systematically shelling the crossing, but Granddad counted the interval between shells, and held back until he calculated that he had a few moments, then galloped across, just making it before the next salvo came down. This story corresponds closely with an incident recounted by Lieutenant P B Berliner, the battalion transport officer at that time, who describes how during an attempt to get rations to the troops on the night of 22 March 1918 (during the great German offensive), an attempt to retrieve a bogged field kitchen caused a ‘frightful clatter’ which caused the support company to open fire, thinking it was a German tank.

The Germans clearly must have heard it too, as they opened fire with a battery of 5.9’s traversing down the road in the forest fortunately just ahead of us all the way down to the cross roads where they concentrated all four guns. When we got within about fifty yards, we waited until all four rounds had come over & then hared around the corner to the right & got clear.

So being in the transport section wasn’t altogether a ‘cushy’ option! Granddad told me another story of the ‘Great Push’ by the Germans in Spring 1918. The Germans almost reached Amiens, with the British retreating before them. Granddad decided that his battalion would need a hot meal, so rounded up every scrap of food he could find and put it into a giant stew, which perhaps didn’t smell too good. At any rate when the Germans caught a whiff of it they retreated and so the British army was saved! Granddad may have exaggerated his part in the German defeat slightly. He also talked a little about the execution of soldiers found guilty of ‘cowardice.’ He didn’t actually say he took part in a firing squad, but described how at an execution the men’s rifles were taken away, loaded with one round, and then returned. One man’s rifle was loaded with a blank cartridge, so that each man could comfort himself with the thought that he had the blank round, and had therefore not fired the fatal shot. However, Granddad said that it was possible to tell if your rifle was firing a live or a blank round, so the process was pointless. Of course, this could well have been only soldiers’ gossip. No man of either the 1/7th or 2/7th Londons was shot during the War, but Robert Loveless Barker of the 1/6th Londons, and Frederick William Slade of the 2/6th Londons, were shot, in 1916 and 1917. Since these battalions were in the same brigades as the 1/7th and 2/7th respectively, Granddad would have been aware of the executions. These are the only details that I can remember of Granddad’s war service, although there are a number of published and unpublished personal accounts by people who served in the Shiny Seventh, including two by transport officers, whom Granddad must have known. I think Granddad was discharged in 1919, in which year he and Grandma moved to Great Yarmouth. Granddad was awarded the usual two medals – the British War and Victory Medals – which we still have, along with his army-issue spurs.

Photographs of Grandfather in uniform and at his wedding also of his medals and spurs

Front

George Frederick Harvey

Photograph

Portrait photograph of George Frederick Harvey in uniform

Photograph of George Frederick Harvey in uniform

Memorabilia

Army issue spurs given to George Frederick Harvey

photograph of the spurs worn by George Frederick Harvey.

George Frederick Harvey's wedding day 1915

Photograph of wedding day George married shortly before enlisting in 1915

George Frederick Harvey's wedding photograph

Medal

George Frederick Harvey's War and Victory medals

CONTRIBUTOR

John Rumsby

DATE

1915 - 1919

LANGUAGE

eng

ITEMS

5

INSTITUTION

Europeana 1914-1918

PROGRESS

METADATA

Discover Similar Stories

DURING THE WAR IN CRETE

1 Item

ΦΩΤΟΓΡΑΦΙΑ || Στην φωτογραφία απεικονίζονται, αριστερά, ο Δημήτρης Βλοντάκης και, δεξιά, ο Ιωάννης Φαλδαμής, αρραβωνιαστικός της αδελφής του Βασιλική, καθισμένοι, με κρητική στολή. Φωτογρ. Μεγαλοοικονόμου “Η Πρόοδος”, Πλατεία Ελ.Βενιζέλου, Χανιά Κρήτης. Η φωτογραφία χρονολογείται μεταξύ 1914-1918. Οι 2 άντρες φορούν κρητική στολή εποχής, ο δε Βλοντάκης φοράει ένα καπότο με πλούσιο γιακά. Αξιοσημείωτο είναι ο μουστακοδέτης των εικονιζόμενων. Ο μουστακοδέτης ήταν ταινία με την οποία οι παλιότεροι έδεναν τη νύχτα το μουστάκι για να πάρει ορισμένο σχήμα. Το πρωί, το έστριβαν εκ νέου βάζοντας ένα είδος ζελέ “μαντεκε”. Για την μικρή “ιστορία”, ο Βλοντάκης είχε ετοιμαστεί για τη φωτογραφία στο σπίτι της αρραβωνιαστικιάς του, Αθηνά Θεοδωράκη που διέμενε στη Χαλέπα. || || ΙΩΑΝΝΗΣ ΦΑΛΔΑΜΗΣ ΚΑΙ ΔΗΜΗΤΡΗΣ ΒΛΟΝΤΑΚΗΣ || Photograph || Front

Leaser & George Samuels | two brothers killed in the war and listed in the British Jewry Book of Honour

7 Items

Transcript of interview with Joan Kalb

My Grandfather George Brien | a cook who survived the War

8 Items

Crucifix made out of bullets ; Holy Water container; Wooden clogs as a keepsake (an indication of him being in or near the Benelux region) ; Brooch made of 2 French coins ; Postcards || My Grandfather George Brien was born in the 1870s. I'm not sure what regiment he was part of, but he ended up being a cook throughout the War and survived it. This may have helped save him, as it meant he was away from the front lines the entire time. He joined up during the 1913 Lockout. He had been working for a train company, but signed up to pay to feed his family. He would have been deployed in France. One item he had was a crucifix made out of bullets. He probably did not make it himself. Another was a small Holy Water container which would have been French as it had a Fleur de Lis crest on it. He also brought a brooch made out of 2 French coins back to his wife. I have several postcards to his mother, father and wife and daughter. No locations are given in them. His handwriting is also very similar to mine. One postcard is of Edith Cavell. He had lots of Daily Mail postcards and bought lots of books of cards after the war. We think he came home after the war in 1919, as his attestation papers suggest this. I always remember him retired in the 1940s. He received an ex-serviceman's house in Killester on the Howth Road in Dublin, Ireland. I'm not sure if he ever worked again. My best memory of him is him doing the gardening. My mother would have been 8 in 1916 during the Easter Rising, when she had to get across the city from Howth to Rathmines in Dublin.He died in the 1960s