Someone else is currently editing this document

Only one person can work on a document at a time

TRANSCRIPTION

– Wilhelm dead – Berta”. Mother packed essentials for herself and for me, put on her black

costume and asked the neighbour to look after house and livestock during our absence. Then

we set off on foot to the station. In the forest she removed her hat, attached it to the wovenstraw

travelling bag and swung bag with hat up on her head. Everything was as always except

that she wept the whole way, also at the station and in the train. The ticket collector and

passengers we encountered made way for her respectfully and left us undisturbed. A weeping

woman in mourning holding a child by the hand – this was at the time a familiar sight, a

typical street scene, so to speak. I just kept looking at my mother during the journey; I could

not cry with her, although I had been fond of Wilhelm. That he was now dead only gradually

sank in. I did not ask any questions. Mother could not have answered them anyway, although

she must have suspected what had happened. In Enzberg we found grandmother and Aunt

Berta weeping. Neighbours were there too, to help and to mourn with them. I was not allowed

to see the corpse. They gave me small jobs to do in the kitchen and in the stable which I had

always liked doing. This time I did not enjoy them. I felt hurt that they did not confide in me.

Something special must have happened: why was I kept out of the room? Why did they not

tell me? I was no longer a small child, after all. When mother brought me to bed, I plucked up

my courage and asked what Uncle Wilhelm had died of. She was silent for a while, reflecting.

Then she told me the truth. He was in a desperate situation, could see no way out and took his

life. Two days before he did that, a commission had come to the farm to demand that he hand

over so and so many hundredweight of corn and potatoes by a certain date. Wilhelm had had

an argument with the men and shown them the almost empty potato cellar. Then they

threatened to put him into prison. It had been a very serious dispute.

He now lay in his coffin, in a white shirt, surrounded by all the spring flowers in bloom in

the garden, his hair still jet-black, his white face carefully shaven, his fine-boned hands folded

on his breast. Silence and peace now reigned around him. Aunt Berta and grandmother spoke

to the parson. An ancient ecclesiastical law stipulated that nobody who had committed suicide

could be buried in hallowed ground. Some villagers believed this rule ought to be observed

and spoke out against Wilhelm being buried in the Enzberg cemetery. The parson comforted

grandmother, however. He told her that since 1900 the law was no longer in force and that

Wilhelm could therefore be interred in the grave of his ancestors. So she was spared this pain

at least. The parson also saw to it that the funeral service was conducted according to the

custom with prayers, sermon and last blessing. A choir of schoolchildren sang as we –

grandmother, her four daughters and I – accompanied Wilhelm on his final journey. The men

82

Language(s) of Transcription

LOCATION

Germany, Wuerttemberg, Hohenklingen, Enzberg (48.9347, 8.79886)

Story Location

ABOUT THIS DOCUMENT

Document Date

Document Type

Document Description

Language of Description

Keywords

External Web Resources

People

Wilhelm Kopp (Death: 04/05/1917, Enzberg)

Berta Kopp

STORY INFORMATION

Title

A German Childhood in the First World War by Else Wuergau

Source

UGC

Contributor

europeana19141918:agent/7b885d3c89fea22cc4464b11e351687a

Date

1914-08

1918-11

Type

Story

Language

deu

eng

Deutsch

English

Country

Europe

DataProvider

Europeana 1914-1918

Provider

Europeana 1914-1918

Rights

http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/DatasetName

2020601_Ag_ErsterWeltkrieg_EU

Begin

1914-08

End

1918-11

Language

mul

Agent

Friedrich Rutsch | europeana19141918:agent/6dc9dd3b90b0cfd88a619a7fd81bc8ed

Rainer Würgau | europeana19141918:agent/7b885d3c89fea22cc4464b11e351687a

Else Rutsch | europeana19141918:agent/c6ff6e707355ad2e93a0c7a45c442b0d

Created

2019-09-11T08:28:08.511Z

2020-02-25T08:25:27.597Z

2016-10-13 05:32:07 UTC

2016-10-13 05:53:20 UTC

Provenance

INTERNET

Story Description

English translation of Eine Kindheit im Ersten Weltkrieg by Else Wuergau The book deals with the impact of the beginning of the war on the idyllic life of a large family of farmers. The main characters are the parents of the narrator: the father a village schoolteacher, from 1916 medical orderly at the Somme front, and the widowed grandmother with her six children. Three of the four daughters have families of their own; the youngest tends to the wounded and becomes a Red Cross nurse. The unmarried eldest son manages the large family farm in Enzberg and is therefore dispensed from military service. The youngest boy, only fifteen years old at the outbreak of the war, joins up voluntarily. In 1917 the eldest becomes unable to withstand the burden of his responsibilities and puts an end to his life. The farm has to be sold; the purchaser pays in war bonds, the value of which are shortly afterwards reduced to virtually nothing. The youngest son is killed in action in Belgium just before the armistice. Available in PDF (13 MB) => http://www.kindheit.stefanmart.de/index_en.html

TRANSCRIPTION

LOCATION

DESCRIPTION

PEOPLE

STORY INFO

TUTORIAL

– Wilhelm dead – Berta”. Mother packed essentials for herself and for me, put on her black

costume and asked the neighbour to look after house and livestock during our absence. Then

we set off on foot to the station. In the forest she removed her hat, attached it to the wovenstraw

travelling bag and swung bag with hat up on her head. Everything was as always except

that she wept the whole way, also at the station and in the train. The ticket collector and

passengers we encountered made way for her respectfully and left us undisturbed. A weeping

woman in mourning holding a child by the hand – this was at the time a familiar sight, a

typical street scene, so to speak. I just kept looking at my mother during the journey; I could

not cry with her, although I had been fond of Wilhelm. That he was now dead only gradually

sank in. I did not ask any questions. Mother could not have answered them anyway, although

she must have suspected what had happened. In Enzberg we found grandmother and Aunt

Berta weeping. Neighbours were there too, to help and to mourn with them. I was not allowed

to see the corpse. They gave me small jobs to do in the kitchen and in the stable which I had

always liked doing. This time I did not enjoy them. I felt hurt that they did not confide in me.

Something special must have happened: why was I kept out of the room? Why did they not

tell me? I was no longer a small child, after all. When mother brought me to bed, I plucked up

my courage and asked what Uncle Wilhelm had died of. She was silent for a while, reflecting.

Then she told me the truth. He was in a desperate situation, could see no way out and took his

life. Two days before he did that, a commission had come to the farm to demand that he hand

over so and so many hundredweight of corn and potatoes by a certain date. Wilhelm had had

an argument with the men and shown them the almost empty potato cellar. Then they

threatened to put him into prison. It had been a very serious dispute.

He now lay in his coffin, in a white shirt, surrounded by all the spring flowers in bloom in

the garden, his hair still jet-black, his white face carefully shaven, his fine-boned hands folded

on his breast. Silence and peace now reigned around him. Aunt Berta and grandmother spoke

to the parson. An ancient ecclesiastical law stipulated that nobody who had committed suicide

could be buried in hallowed ground. Some villagers believed this rule ought to be observed

and spoke out against Wilhelm being buried in the Enzberg cemetery. The parson comforted

grandmother, however. He told her that since 1900 the law was no longer in force and that

Wilhelm could therefore be interred in the grave of his ancestors. So she was spared this pain

at least. The parson also saw to it that the funeral service was conducted according to the

custom with prayers, sermon and last blessing. A choir of schoolchildren sang as we –

grandmother, her four daughters and I – accompanied Wilhelm on his final journey. The men

82

- English (English)

– Wilhelm dead – Berta”. Mother packed essentials for herself and for me, put on her black

costume and asked the neighbour to look after house and livestock during our absence. Then

we set off on foot to the station. In the forest she removed her hat, attached it to the wovenstraw

travelling bag and swung bag with hat up on her head. Everything was as always except

that she wept the whole way, also at the station and in the train. The ticket collector and

passengers we encountered made way for her respectfully and left us undisturbed. A weeping

woman in mourning holding a child by the hand – this was at the time a familiar sight, a

typical street scene, so to speak. I just kept looking at my mother during the journey; I could

not cry with her, although I had been fond of Wilhelm. That he was now dead only gradually

sank in. I did not ask any questions. Mother could not have answered them anyway, although

she must have suspected what had happened. In Enzberg we found grandmother and Aunt

Berta weeping. Neighbours were there too, to help and to mourn with them. I was not allowed

to see the corpse. They gave me small jobs to do in the kitchen and in the stable which I had

always liked doing. This time I did not enjoy them. I felt hurt that they did not confide in me.

Something special must have happened: why was I kept out of the room? Why did they not

tell me? I was no longer a small child, after all. When mother brought me to bed, I plucked up

my courage and asked what Uncle Wilhelm had died of. She was silent for a while, reflecting.

Then she told me the truth. He was in a desperate situation, could see no way out and took his

life. Two days before he did that, a commission had come to the farm to demand that he hand

over so and so many hundredweight of corn and potatoes by a certain date. Wilhelm had had

an argument with the men and shown them the almost empty potato cellar. Then they

threatened to put him into prison. It had been a very serious dispute.

He now lay in his coffin, in a white shirt, surrounded by all the spring flowers in bloom in

the garden, his hair still jet-black, his white face carefully shaven, his fine-boned hands folded

on his breast. Silence and peace now reigned around him. Aunt Berta and grandmother spoke

to the parson. An ancient ecclesiastical law stipulated that nobody who had committed suicide

could be buried in hallowed ground. Some villagers believed this rule ought to be observed

and spoke out against Wilhelm being buried in the Enzberg cemetery. The parson comforted

grandmother, however. He told her that since 1900 the law was no longer in force and that

Wilhelm could therefore be interred in the grave of his ancestors. So she was spared this pain

at least. The parson also saw to it that the funeral service was conducted according to the

custom with prayers, sermon and last blessing. A choir of schoolchildren sang as we –

grandmother, her four daughters and I – accompanied Wilhelm on his final journey. The men

82

Language(s) of Transcription

English Translation

Transcription History

– Wilhelm dead – Berta”. Mother packed essentials for herself and for me, put on her black costume and asked the neighbour to look after house and livestock during our absence. Then we set off on foot to the station. In the forest she removed her hat, attached it to the wovenstraw travelling bag and swung bag with hat up on her head. Everything was as always except that she wept the whole way, also at the station and in the train. The ticket collector and passengers we encountered made way for her respectfully and left us undisturbed. A weeping woman in mourning holding a child by the hand – this was at the time a familiar sight, a typical street scene, so to speak. I just kept looking at my mother during the journey; I could not cry with her, although I had been fond of Wilhelm. That he was now dead only gradually sank in. I did not ask any questions. Mother could not have answered them anyway, although she must have suspected what had happened. In Enzberg we found grandmother and Aunt Berta weeping. Neighbours were there too, to help and to mourn with them. I was not allowed to see the corpse. They gave me small jobs to do in the kitchen and in the stable which I had always liked doing. This time I did not enjoy them. I felt hurt that they did not confide in me. Something special must have happened: why was I kept out of the room? Why did they not tell me? I was no longer a small child, after all. When mother brought me to bed, I plucked up my courage and asked what Uncle Wilhelm had died of. She was silent for a while, reflecting. Then she told me the truth. He was in a desperate situation, could see no way out and took his life. Two days before he did that, a commission had come to the farm to demand that he hand over so and so many hundredweight of corn and potatoes by a certain date. Wilhelm had had an argument with the men and shown them the almost empty potato cellar. Then they threatened to put him into prison. It had been a very serious dispute. He now lay in his coffin, in a white shirt, surrounded by all the spring flowers in bloom in the garden, his hair still jet-black, his white face carefully shaven, his fine-boned hands folded on his breast. Silence and peace now reigned around him. Aunt Berta and grandmother spoke to the parson. An ancient ecclesiastical law stipulated that nobody who had committed suicide could be buried in hallowed ground. Some villagers believed this rule ought to be observed and spoke out against Wilhelm being buried in the Enzberg cemetery. The parson comforted grandmother, however. He told her that since 1900 the law was no longer in force and that Wilhelm could therefore be interred in the grave of his ancestors. So she was spared this pain at least. The parson also saw to it that the funeral service was conducted according to the custom with prayers, sermon and last blessing. A choir of schoolchildren sang as we – grandmother, her four daughters and I – accompanied Wilhelm on his final journey. The men 82

– Wilhelm dead – Berta”. Mother packed essentials for herself and for me, put on her black costume and asked the neighbour to look after house and livestock during our absence. Then we set off on foot to the station. In the forest she removed her hat, attached it to the wovenstraw travelling bag and swung bag with hat up on her head. Everything was as always except that she wept the whole way, also at the station and in the train. The ticket collector and passengers we encountered made way for her respectfully and left us undisturbed. A weeping woman in mourning holding a child by the hand – this was at the time a familiar sight, a typical street scene, so to speak. I just kept looking at my mother during the journey; I could not cry with her, although I had been fond of Wilhelm. That he was now dead only gradually sank in. I did not ask any questions. Mother could not have answered them anyway, although she must have suspected what had happened. In Enzberg we found grandmother and Aunt Berta weeping. Neighbours were there too, to help and to mourn with them. I was not allowed to see the corpse. They gave me small jobs to do in the kitchen and in the stable which I had always liked doing. This time I did not enjoy them. I felt hurt that they did not confide in me. Something special must have happened: why was I kept out of the room? Why did they not tell me? I was no longer a small child, after all. When mother brought me to bed, I plucked up my courage and asked what Uncle Wilhelm had died of. She was silent for a while, reflecting. Then she told me the truth. He was in a desperate situation, could see no way out and took his life. Two days before he did that, a commission had come to the farm to demand that he hand over so and so many hundredweight of corn and potatoes by a certain date. Wilhelm had had an argument with the men and shown them the almost empty potato cellar. Then they threatened to put him into prison. It had been a very serious dispute. He now lay in his coffin, in a white shirt, surrounded by all the spring flowers in bloom in the garden, his hair still jet-black, his white face carefully shaven, his fine-boned hands folded on his breast. Silence and peace now reigned around him. Aunt Berta and grandmother spoke to the parson. An ancient ecclesiastical law stipulated that nobody who had committed suicide could be buried in hallowed ground. Some villagers believed this rule ought to be observed and spoke out against Wilhelm being buried in the Enzberg cemetery. The parson comforted grandmother, however. He told her that since 1900 the law was no longer in force and that Wilhelm could therefore be interred in the grave of his ancestors. So she was spared this pain at least. The parson also saw to it that the funeral service was conducted according to the custom with prayers, sermon and last blessing. A choir of schoolchildren sang as we – grandmother, her four daughters and I – accompanied Wilhelm on his final journey. The men 82

English Translation

English translation of Eine Kindheit im Ersten Weltkrieg by Else Wuergau The book deals with the impact of the beginning of the war on the idyllic life of a large family of farmers.

The main characters are the parents of the narrator: the father a village schoolteacher, from 1916 medical orderly at the Somme front, and the widowed grandmother with her six children.

Three of the four daughters have families of their own; the youngest tends to the wounded and becomes a Red Cross nurse.

The unmarried eldest son manages the large family farm in Enzberg and is therefore dispensed from military service.

The youngest boy, only fifteen years old at the outbreak of the war, joins up voluntarily.

In 1917 the eldest becomes unable to withstand the burden of his responsibilities and puts an end to his life.

The farm has to be sold; the purchaser pays in war bonds, the value of which are shortly afterwards reduced to virtually nothing.

The youngest son is killed in action in Belgium just before the armistice.

Available in PDF (13 MB) => http://www.kindheit.stefanmart.de/index_en.html

Automatically Identified Enrichments

Verify Automatically Identified Enrichments

Verify Automatically Identified Locations

Verify Automatically Identified Persons

Enrichment Mode

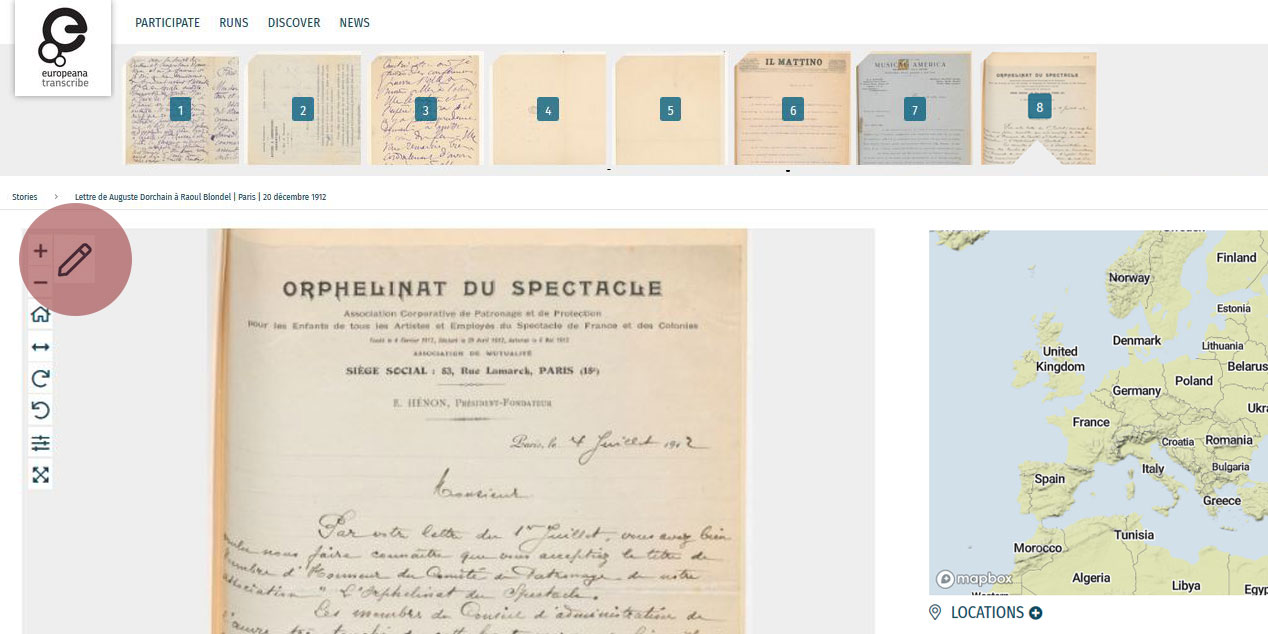

Edit your workspace view by using the top-right menu.

You can have the white Activity Panel docked to the right (default) , to the bottom , or as an independent overlay . If you just want to view the image, you can hide the panel using the minimise button , and then re-open it with the pen button. Adjust the size and position of your Activity Panel according to your preferences.

You enrich documents by following a step-by-step process.

Make sure you regularly save your enrichments in each step to avoid the risk of losing your work.

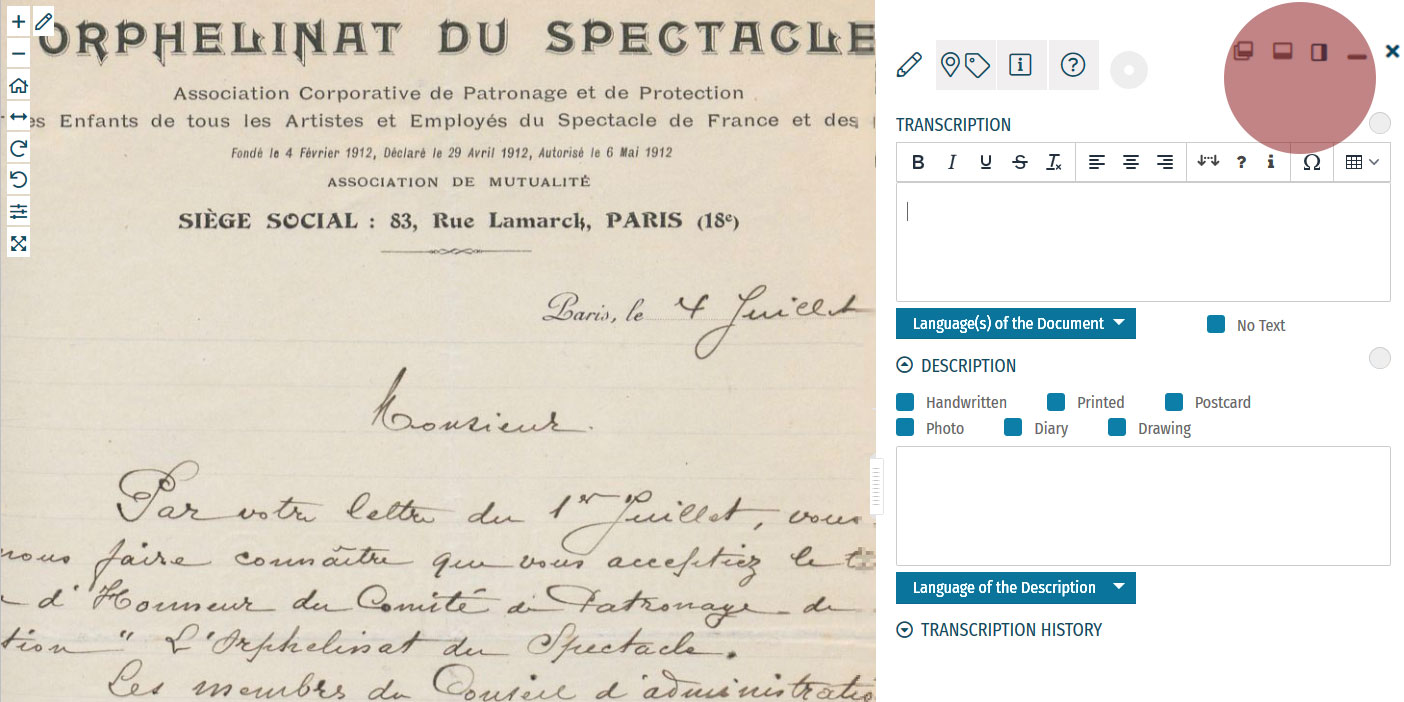

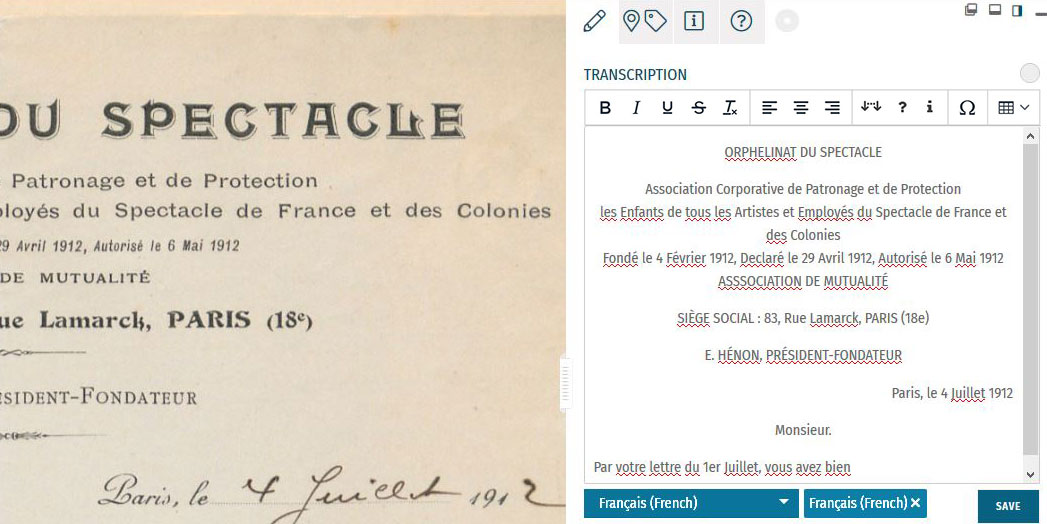

Step 1: Transcription

To start a transcription, select the transcription tab at the top menu of the Activity Panel. Click inside the box underneath the heading TRANSCRIPTION and start writing your transcription. When needed, use the toolbar to format your text and to add special characters and tables. A guide to the transcription toolbar is available in the Formatting section of this tutorial.

Identify the language(s) of the text using the dropdown list under the transcription box. You can select multiple languages at once.

If the item has no text to transcribe, tick the checkbox ‘No Text’.

Once you have finished your transcription, click SAVE.

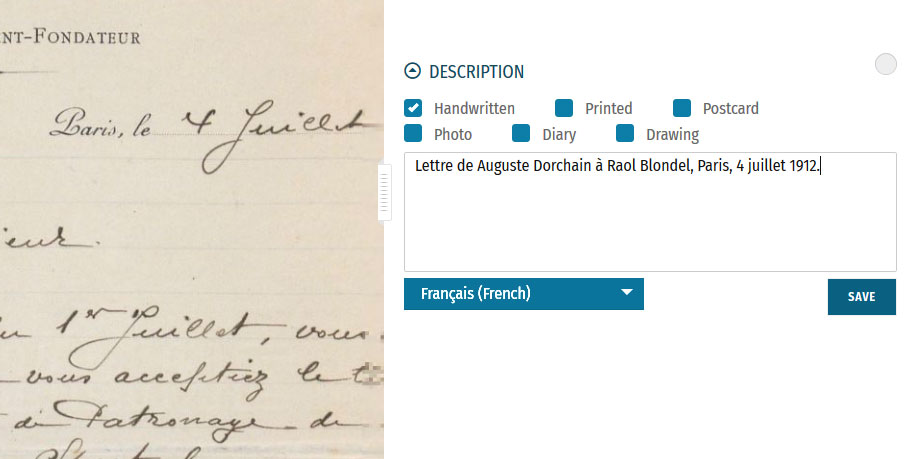

Step 2: Description

You can add a description to the item underneath the Transcription section.

The first task is to identify what type of document the item is: a handwritten or printed document, a postcard, photo, drawing and/or part of a diary. Tick the category which best applies to the item. Multiple categories can be selected at once.

The second task is to write a description of the contents. Click inside the box underneath the heading DESCRIPTION. Here, you can write what the item is, what it is about, and specify the images and objects that appear in the item.

Identify the language of the description text that you wrote using the dropdown list underneath. You can only select one language.

Once you have finished your description, click SAVE.

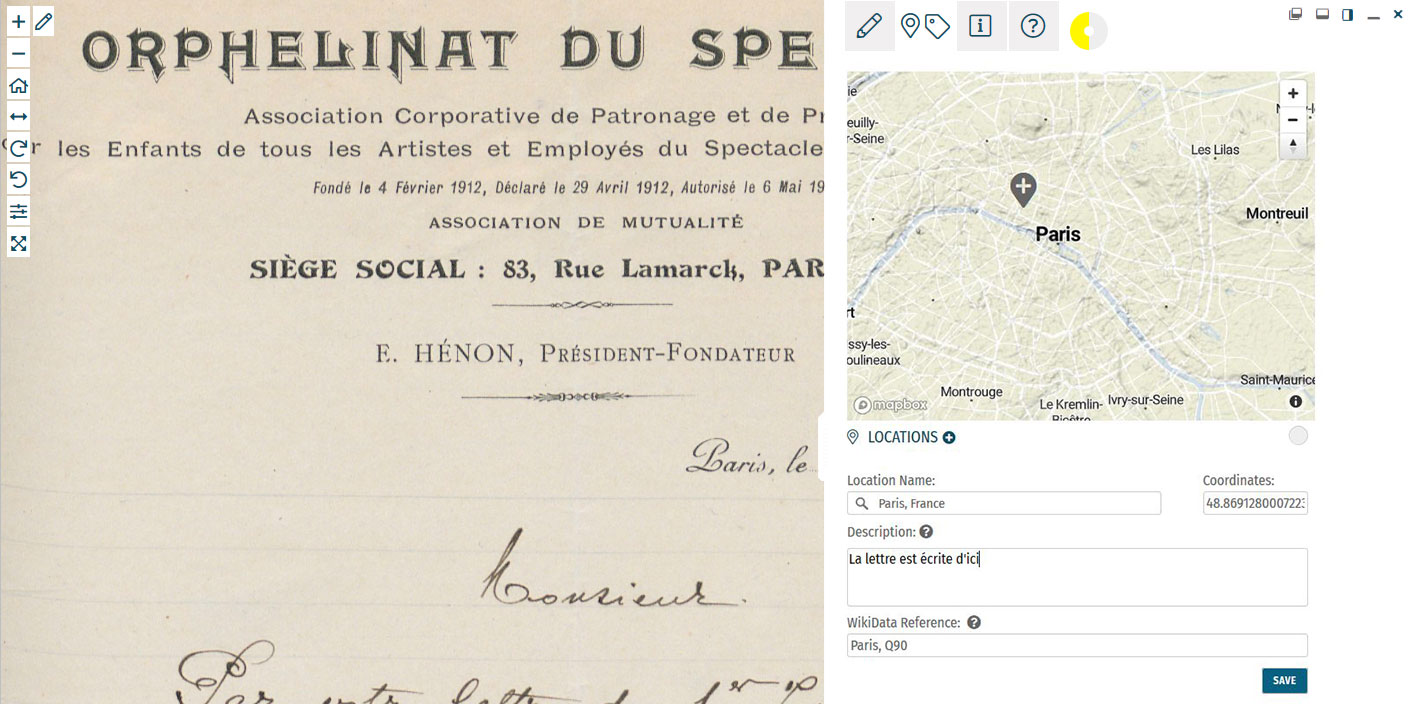

Step 3: Location

If you find a location mentioned or recognise a place in the item, you can create a geotag and pin it to the item map. Multiple locations can be attached to the item. To tag locations, select the tagging tab at the top menu of the Activity Panel. Click the plus next to the heading LOCATIONS. Type the location into the search bar and select the result that best applies. A new pin will be placed into the map. The location name should be a clear georeference, e.g. a country, city or address. Make adjustments to the location name if necessary. You can also adjust the position of the pin by dragging it on the map. If you want to add further details to the location, you can write a (short) description. This could include extra information about the geotag (e.g. the building name or a significant event that took place at the location) or the relevance of the place to the item (e.g. the hometown of the author). You can also add a Wikidata reference to link the location to a stable source. Search for the reference using the Wikidata fields. Once you have finished your location tag, click SAVE. You can find the place(s) tagged to the item in grey at the bottom of the Location(s) section.Step 4: Tagging

Below the Locations section is the Tagging section, where you can add the following annotations:

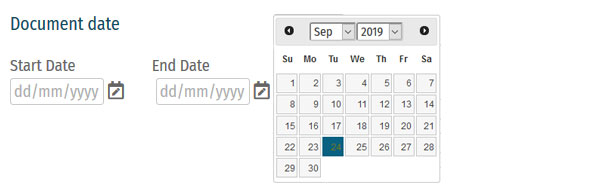

Document Date:

Document Date:Here, you can add dates that correspond to the item. This could include the dates mentioned in the text (e.g. in diary pages), the date of a related historical event (e.g. the end of WWI), or when the item was created (e.g. from a dated signature on an illustration). You can either define this as a single date or as a longer time frame.

To tag dates to the item, write the start and end dates in DD/MM/YYYY format in the fields or select the dates by clicking on the calendar.

If you only have one date to add, insert the same date into both start and end fields.

If you don’t know the exact days, you can also tag the date on the scale of months (MM/YYYY) or years (YYYY).

Once you have finished your date tag, click SAVE DATE.

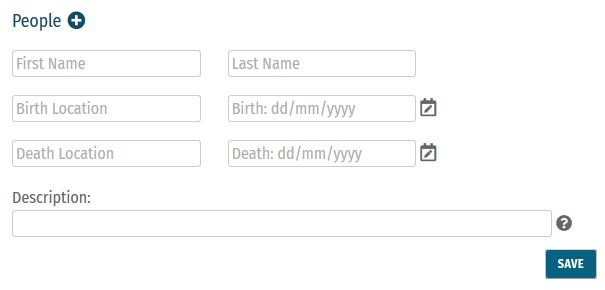

People:

People:People mentioned as creators or subjects in the item can also be tagged. Depending on the information you might have, you can enter the person’s first and last names, as well as their dates of birth and death. There is also the option to write a short description of the person, explaining who they are or their relevance to the item, e.g. the person’s occupation or their relation to another tagged person.

Multiple people can be tagged to one item.

Once you have finished your person tag, click SAVE.

Keywords:

Keywords:Here, you can freely add keywords related to the topic and content of the item. This could include particular themes (e.g. art, music, war), subjects (e.g. children, cooking, France), or particular historical affiliations (e.g. 20th century, Austro-Hungarian Empire, Fall of the Iron Curtain).

Multiple keywords can be added and they can be written in any language.

Write your keyword tag into the field and click SAVE.

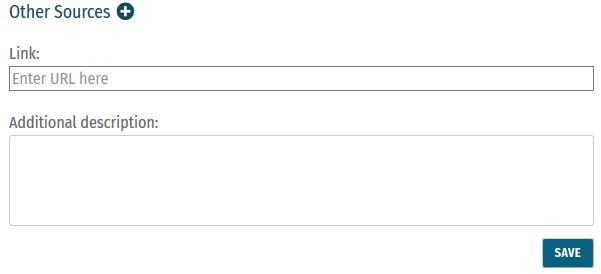

Other Sources:

Other Sources:External websites with information about the item’s content can be linked here. This could include links to further data about a person mentioned, a particular historical event or links to digital versions of newspapers that appear in photos or clippings in a notebook.

To add a link, click the plus next to the heading ‘Other Sources’. Enter the URL into the Link field, and write a short description of this link in the Additional Description field.

Multiple links can be tagged to one item.

Once you have finished your tag, click SAVE.

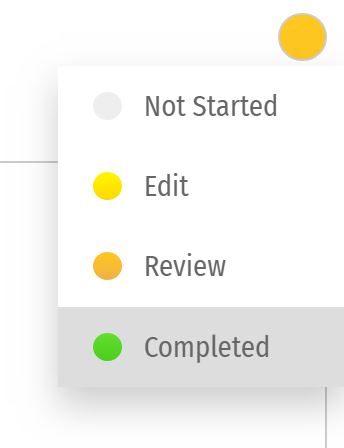

Step 5: Mark for Review

Once you have saved your contribution, the task will automatically change to the Edit status. If you think the task is finished, you can mark it for review. Note that you have to be at Runner level or above to do this (see: Miles and Levels). Click on the yellow circle next to the section heading and select Review in the list that appears. The task now needs to go under Review by another volunteer.Formatting

Review

All enrichments need to be edited and reviewed by more than one volunteer to ensure that they are as accurate as possible.

Only Sprinters and Champions can edit tasks in the Review stage and mark them as Complete. (see: Miles and Levels)

You can review a task (Transcription, Description, Locations, or Tagging) when the circle next to the heading is coloured orange .

During the review process, pay close attention to the following requirements:

All enrichments need to be edited and reviewed by more than one volunteer to ensure that they are as accurate as possible.

Only Sprinters and Champions can edit tasks in the Review stage and mark them as Complete. (see: Miles and Levels)

You can review a task (Transcription, Description, Locations, or Tagging) when the circle next to the heading is coloured orange .

During the review process, pay close attention to the following requirements:

-

- Transcription: The complete text in the item has been properly transcribed and the transcription is formatted as accurately as possible. The correct language(s) are selected and the transcription contains no missing or unclear icons.

-

- Description: The description is accurate and detailed (especially items without text to transcribe, e.g. photos), and the appropriate categories have been ticked.

-

- Location(s): All locations have been correctly tagged. The location name is accurate and matches the coordinates and the pin on the map. The description is clear and concise, and the Wikidata reference (if any) is correct.

-

- Tagging: Document dates are completed and as precise as possible. All mentioned people are tagged and their data is correct. All added keywords are applicable to the item, and other sources have accurate information and functioning links.

Completion Statuses

| GREY |

| 1. NOT STARTED |

| Tasks have not been started. |

| YELLOW |

| 2. EDIT MODE |

| Tasks have been started, but not yet finished. Additions and edits can still be made. |

| ORANGE |

| 3. REVIEW |

| Tasks are finished, but need final review by Sprinter or Champion transcribers. |

| GREEN |

| 4. COMPLETED |

| Tasks have been fully completed and reviewed. No further changes need to be made. |

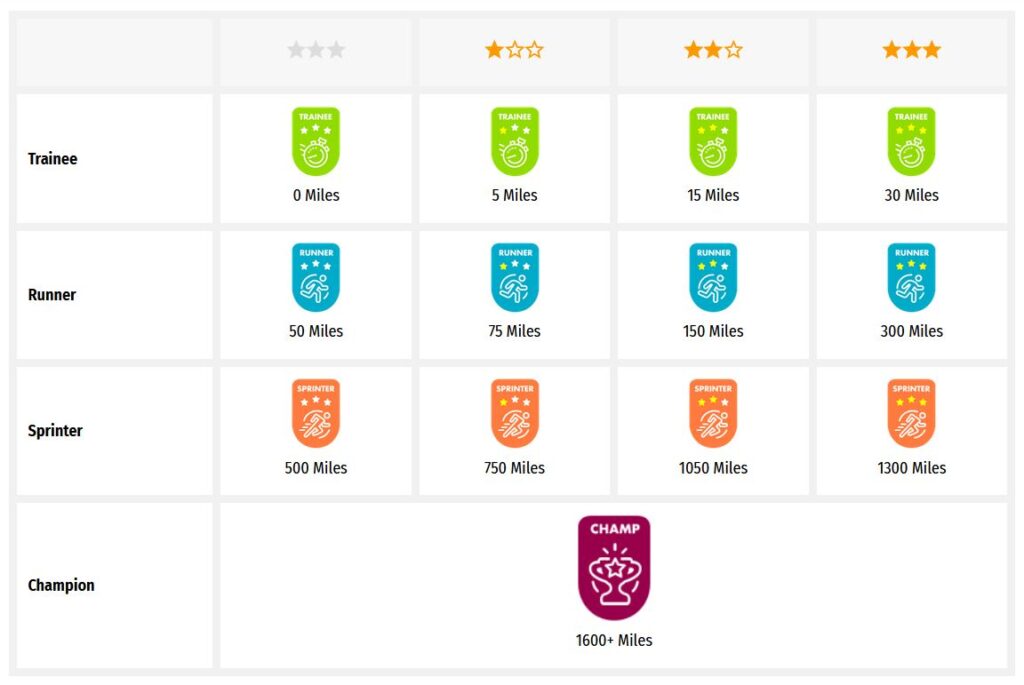

Miles and Levels

Transcribathon is a competitive marathon. You do not enrich documents alone, but compete and work with other volunteers to ensure the quality of your work. When you first create a Transcribathon account, you only have the ability to start and edit tasks. The more you enrich documents, the closer you become to advancing to a higher level, which can unlock abilities like reviewing and completing tasks.| Level | Abilities |

|---|---|

| Trainee | Basic abilities: start and edit tasks |

| Runner | Basic abilities, mark finished tasks for review |

| Sprinter | All Runner abilities, mark reviewed annotations as completed |

| Champion | All Sprinter abilities, mark reviewed transcriptions as completed |

| Tasks | Miles Received |

|---|---|

| Transcription | 1 Mile for every 300 characters transcribed |

| Description | 1 Mile for every 5 Descriptions added |

| Location | 1 Mile for every 5 Locations added |

| Tagging | 1 Mile for every 5 Tags added |

| Reviewing | 1 Mile for every 10 items marked as complete |