World War 1

Picture of soldiers in a trench. Royal Irish Rifles ration party Somme July 1916

My grandfather is one of the men in the picture. He was a brave brave fighter proud to serve his country. We miss him every single day.

Somme

Photograph

Royal Irish Rifles ration party Somme July 1916

CONTRIBUTOR

Rebecca

DATE

1916

LANGUAGE

eng

ITEMS

1

INSTITUTION

Europeana 1914-1918

PROGRESS

METADATA

Discover Similar Stories

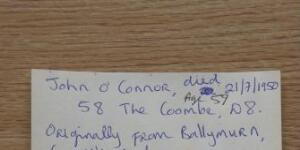

World War 1 Soldier: John O'Connor

80 Items

Attached are a Guinness employees soldiers records book with my great grandfather's name. Also there are a couple of pictures of him. John O'Connor was born in Wexford served in the Irish Guards and was a prisoner of war (also find attached prisoner of war records). He worked in St James Gate and lost his leg in the war. || -Photos -Guinness employee soldier roll -Prisoner of war record book

World War 1 - An Unkept Promise

218 Items

Chapter 1 presents historical background information about the circumstances which caused the war and how it impacted my grandfather. Chapter 2 Offers the reader an insight into the Royal Field Artillery and will help them understand the journal entries In April I'll release two additional chapters - The Battle of Mons and the retreat. || I was given my grandfather's WWI journal as well as other documents. My grandfather served in the Royal Field Artillery from 1905 to 1919 and fought in the early battles of the war. It was a letter he wrote in 1945 that inspired me to write his story. It begins with historical background information before presenting chapters on each of the early battles from Mons to Second Ypres. Obtaining the journal gave me insight into a man I didn't know very well. I called him grampy but I did not know him on a personal level. He died in 1960 when I was 13 years old but through his journal I got to know him. On the 6th of September 2013 I traveled to London and donated my grandfather's documents to the Imperial War Museum.

World War 1 - An Ukept Promise

218 Items

A non-fiction account of my grandfather's experiences fighting in the early battles of the war based upon his WWI journal. It has taken me over three years to assemble the information and write an informative historical depiction of The Great War through the experiences of one man who survived. While writing my grandfather's story I wanted to present just enough background information to help the reader fully appreciate the compelling journal entries. By design I my aim was to transport the reader beyond the historical complexities of the war and into the trenches to experience the realities of war experienced by a Royal Field Artillery soldier.